Needing Nourishment

How COVID-19 is shaping local food insecurity

Virginia Smith, 80, wakes up every morning and goes through the same routine she has had for the last four years. She tends to her husband Fred’s daily needs, a necessity after he suffered two …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Needing Nourishment

How COVID-19 is shaping local food insecurity

Virginia Smith, 80, wakes up every morning and goes through the same routine she has had for the last four years. She tends to her husband Fred’s daily needs, a necessity after he suffered two strokes. She showers him, helps him shave, dress and use the restroom. She crushes his medicine which she must add to his pureed food – the only way Fred will take the medication. Finally, their in-home caregiver Nicole arrives, freeing Smith up for a bit before she repeats the same routine at night.

It has also been four years since Smith began benefiting from services provided by local nonprofits. The Houston native moved to the Katy area in 2011 to help her son but after her husband’s strokes and her own heart attack, Smith stayed longer than anticipated. In 2014, her funds ran out. Further emergency surgeries for her husband prevented them from moving back home.

“Social security only goes so far,” Smith said, who currently lives on $547 a month. “I’m on a budget, especially with several medical monthly bills.”

The Smiths face food insecurity like others with limited budgets. Smith said she usually runs out of money by the third week of the month and, like many in the area, has turned to Katy Christian Ministries’ food pantry for help.

“I bought beef this week, for the first time in probably three years,” Smith said. “Mostly everything (I buy) is for (my husband). I don’t even eat the food – I’ll take a little chunk and eat and that’s it. I’m just trying to save money.”

COVID-19’s impact on food demands

Smith has faced food insecurity for a long time and remembers when food banks did not exist.

“Back in my younger days, I had all three of (my children) by myself to raise, and believe me, there were no food pantries,” Smith said. “I’ve gone three to four days without eating so I know what it is to be hungry.”

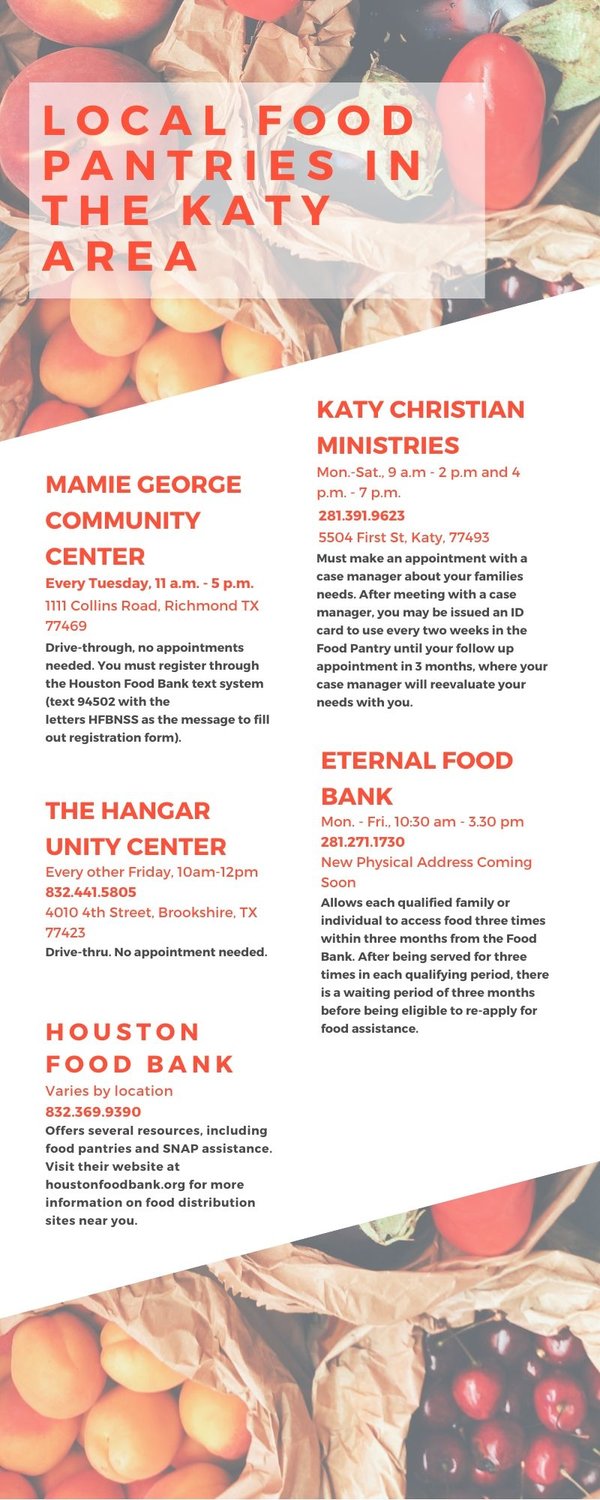

Deysi Crespo, executive director at KCM, said the economic downturn and the increased demand for the nonprofit's food pantry’s services are reminiscent of how KCM came to be 36 years ago. KCM was formed in 1984 by nine churches answering the call to aid families struggling with food insecurity during the 1980s economic downturn.

“We know that these are families that are going through an economic hardship, depending on whatever factor that is that put them in that particular situation. Whether (it’s) loss of employment, hours being reduced, or an illness presented itself, a severe illness, death in the family, and different factors that, unfortunately, no one is exempt from falling into a situation like that,” said Crespo.

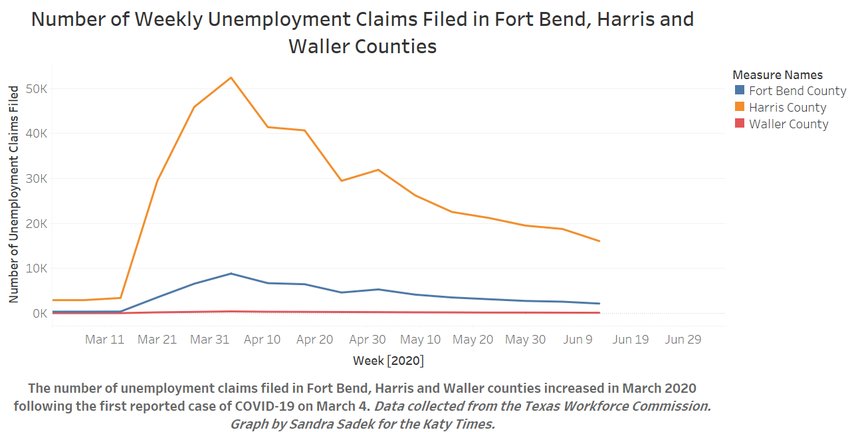

The Texas Workforce Commission reports that as of June 20, 2020, there were 2,219 unemployment claims in Fort Bend County, 17,081 in Harris County, and 141 in Waller County.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, many food pantries have been struggling to meet the rising demand for food assistance brought on by unemployment and other factors.

“You do see unfamiliar faces. We are seeing people that are outside of the people that we usually serve,” said Shayne Baker, who oversees Trini’s Corner Market, a food pantry based out of the Mamie George Community Center in Richmond. “Seeing 100 families each day, we got to know a lot of those families, it was a little bit more personal. And now that we're expanding, there’s a bunch of new faces that we are getting to meet and smile at.”

Adjusting operations for an increased demand

According to 2018 data collected by Feeding America, a nationwide nonprofit that fights food insecurity, there are already 81,310 food insecure people in Fort Bend County alone, with 44% of those people living below the SNAP threshold for poverty. Children are the most affected by this issue with 34,140 food-insecure children in the county, Feeding America reports.

As COVID-19 continues to affect daily lives, food insecurity in Fort Bend County is projected to increase by almost 4%, from 11% in 2018 to 15.7% in 2020, according to Feeding America.

KCM Food Pantry Director Krissy Viau Shetterly said demand at the food pantry due to COVID-19 has been “astounding.” In March 2019, 1,390 households were served; for March 2020, following the start of the pandemic, 2,494 households were served, an increase of nearly 80%.

“You can see in March where the panic really set in, how the numbers just skyrocketed. It has come down a bit but it’s still a lot more than we saw. Of course, I don’t see it going back down anytime soon to anything like we had before,” Shetterly said.

The panic following COVID-19’s outbreak brought about panic in grocery stores, with people stockpiling and leading to food shortages. Thus, more people had to turn to food pantries.

“At the beginning of (the pandemic), we were literally counting how many days’ worth of food we had in the food pantry. We’ve never done that before,” Shetterly said.

Food pantries have adjusted operations to ensure the safety of families, volunteers and employees while continuing to assist. Many have switched over to a drive-thru style of distribution, limiting the number of individuals inside the pantry and reducing contact.

“We do intake through a drive-thru line,” Baker said. “All of our volunteers and staff are working outside in the heat to continue to provide that assistance and then we bring the food directly to the cars on the road, food into the trunk for the cars for the client so that they don't need to get outside of their vehicle or put themselves in any kind of harm's way.”

Others have also reduced their hours to again limit contact as well as give staff and volunteers time to restock. Shetterly said KCM reduced its operational hours from seven and a half hours a day to five hours a day which makes clients more comfortable and helps volunteers.

“That makes (our volunteers) a lot more comfortable also because we have a lot of elderly volunteers, and they don't want to stay at home. They want to stay out, they want to help their neighbors or community and so they're able to still do that and feel comfortable coming to the food pantry,” Shetterly said.

Fighting food insecurity

The nationwide reach of food insecurity in the U.S. has led to many initiatives attempting to tackle the issue. The most well-known governmental food assistance is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program which served 38 million people nationwide in 2019. The Trump administration cut SNAP funding by $17.2 billion in 2019. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced an emergency increase on April 22 to monthly benefits of 40% - about $2 billion.

On May 12, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott also provided over $1 billion in food benefits to families with children who benefited from free and discounted school meals before school closures due to COVID-19.

Andra Tomsa developed Spare USA, an app that rounds up grocery and food delivery bills, donating that round-up to local food banks.

“Beforehand, about 15% of the nation was facing some form of food insecurity, largely, that included families with children, elderly or disabled members,” Tomsa said. “ There are now middle-income middle-class Americans using food banks for the first time because, through no fault of their own, (work) has become sort of obsolete for the time being and that sort of economic impact is going to last for months if not years after.”

Tomsa attributes added demand at food banks to low wages that do not reflect the rising costs of living. She said it is important to support food banks, which have become places of even more essential during the pandemic.

KatyISD and other school districts are also helpful when it comes to fighting food insecurity. The Texas Department of Agriculture authorized school districts to do curbside pickup of meals during the pandemic. KatyISD reports delivering 1,071,169 meals to KatyISD families since March 16.

There are many other ways to aid food banks and pantries during COVID-19 as they face higher numbers of clients needing assistance. Tomsa believes increasing SNAP benefits during the pandemic and even after will mitigate pressure on food banks and redirect people to their local grocery stores, therefore reinvesting in the economy.

Shetterly and Crespo said they normally would encourage volunteering time at food banks and pantries, but the current COVID-19 situation has limited the availability of such opportunities. However, they said donating unique food items can make a huge difference in someone’s diet.

“It’s also being mindful of healthy food choices,” Crespo said. “If someone’s diabetic or has a medical condition, they can’t eat XYZ, maybe we have an alternative. We don't have the luxury to say we have an array of all these healthy choices. But if we're blessed with healthier food choices, then that in itself will be also transforming lives from the medical aspect.”

For many Katy area residents, every day comes down to choosing between bills and food. COVID-19’s impact on society has left many seeking out assistance for the first time.

“I don’t care who you are or how wealthy you are. You never know when you’re gonna need help,” Smith said. “And I thank God for Katy Christian Ministries, and I pray for them every day because right now it’s very difficult.”

Keywords

food insecurity, COVID-19, food pantries, KCM, hunger, nonprofit, rising demands